JATS XML comes up a lot in the scholarly publishing world when it comes to accessibility, preservation, information exchange, and more. But what does it mean, and what is it for?

Alec Smecher, PKP’s Development Associate Director, gives us the run-down in a way that makes sense – even if you’re not an expert in the technical side of scholarly communications. Thank you Alec for taking the time to answer these questions for our audience.

To begin, in simple terms, what is XML?

In scholarly publishing, when people talk about XML, they’re almost always talking about JATS XML. XML is a much bigger subject, so I’ll just talk about JATS. (TEI is another form of XML that’s used in scholarly communication, and there are tons of kinds of XML used in other fields too.)

JATS (Journal Article Tag Set) is a vocabulary that can be used to write a journal article in a way that’s machine readable. When you write an article in a word processor, by convention the title is larger and placed at the top of the first page, which is clearly a title to a human reader. Computers don’t work that way, though, and for them, identifying the title in a word processor document is hard.

Writing an article in JATS form makes it clear – not just for the title, but for abstracts, author identification, figures and captions, parts of citations and so on. There are hundreds of pieces that make up a scholarly article, each with its own conventions, and JATS can make all of this clear.

To put it another way, word processors produce layout formats (they describe what a page looks like without understanding what’s on it), and JATS is a semantic format (it describes what the information is without specifying how it looks on the page).

How is JATS XML used in scholarly publishing?

Once a scholarly article is in a machine readable form like JATS, you can do all kinds of automated things with it. The most important possibilities for most publishers are indexing articles in scholarly indexes, and transforming the articles into HTML or PDF without a lot of manual work.

Articles in JATS are also very good for long-term archiving; it’s easy for computers to work with large collections, and there’s very little overhead in the format compared to something like .docx or .pdf. Understanding what the articles are a thousand years from now will be relatively easy compared to a PDF.

An article in the scholarly ecosystem has to interact with a lot of services, and each interaction has expectations about what kind of data is exchanged and what form it’s in. Many of these services or standards (like NISO MECA and PubMed Central) expect articles in JATS directly; for others, transforming JATS articles into a form they can use is a familiar job.

For example, in Canada, PKP and Érudit together have formed Coalition Publica, which indexes, supports, and distributes Canadian research at institutions across the country. Exchanging data in JATS form allows their various systems to work together in a distributed way.

What are some common concerns about JATS XML in scholarly publishing?

JATS offers a lot of promise – and it’s an excellent standard – but there are good reasons why publishers haven’t universally adopted it.

The biggest challenge is the cost (human or financial) of producing it. Most authors write using word processors, and converting from those formats to JATS is often done with a lot of human effort, as every part of the document needs to be identified and separated from its neighbouring pieces. The JATS standard is extremely fine-grained, and producing a quality JATS document requires expertise and time.

There are expert and AI-aided systems to help produce JATS, and commercial ventures that will take care of the conversion on behalf of journals that don’t have their own resources, but it is still much more expensive to produce than a PDF, and that probably won’t change soon.

Another challenge is that the richness of the JATS vocabulary means that there are often several ways of encoding the same information with varying levels of detail. This reflects the rich variety of metadata in scholarly publishing rather than any fault in JATS, but it does mean that tools to work with JATS have to consider many different forms for the same information.

Many groups and tools working with JATS have decided to limit themselves to a subset of JATS, and there is probably no single tool that accepts all of its forms. This can be frustrating for users who just want to get a job done and have a JATS document in hand.

Finally, there are a lot of misconceptions about JATS. Publishers have often been promised that a lot of problems will go away if they adopt JATS, but that hides a lot of detail under the rug. For example, a publishing pipeline using JATS might replace a laborious desktop publishing workflow used to produce HTML and PDF forms of articles – but in its place they will need templates, which have their own requirements and expertise.

I believe there is still a lack of good, general purpose, free/open source JATS tools, particularly to edit documents, and that those will emerge and strengthen over time. But JATS is not new, and it’s interesting that these have been so slow to mature. I’m sure the complexity of JATS is to blame, and it will be interesting to see if that’s simply too great a barrier for publishers with limited resources.

How does the PKP Community and the Dev Team work together on JATS XML for OJS, OMP, and OPS?

PKP has launched or contributed to many projects related to JATS over the years, including tools to transform word processor documents into JATS (docxConverter, Grobid, Lemon8, OTS), tools or plugins for editing JATS documents (Texture, Libero Editor), and various plugins to present JATS documents to readers (JATSParserPlugin, Lens Galley).

All of these are open-source projects and have benefited from community stewardship. Many OJS-based journals have been able to piece together production JATS workflows in spite of the confusing variety of tools available and their incomplete coverage of the JATS standard.

Historically our plans for JATS have centered on integrating a good editing tool that non-experts can use to work with JATS documents. Unfortunately several of these have foundered before reaching production readiness, and PKP does not foresee the emergence of a good free open source tool in the near future. Therefore we’re looking at other ways to move ahead on JATS workflows, with the help of our XML and technical committees, Coalition Publica, and close partners like Érudit.

What are some milestones to look forward to in this JATS XML work?

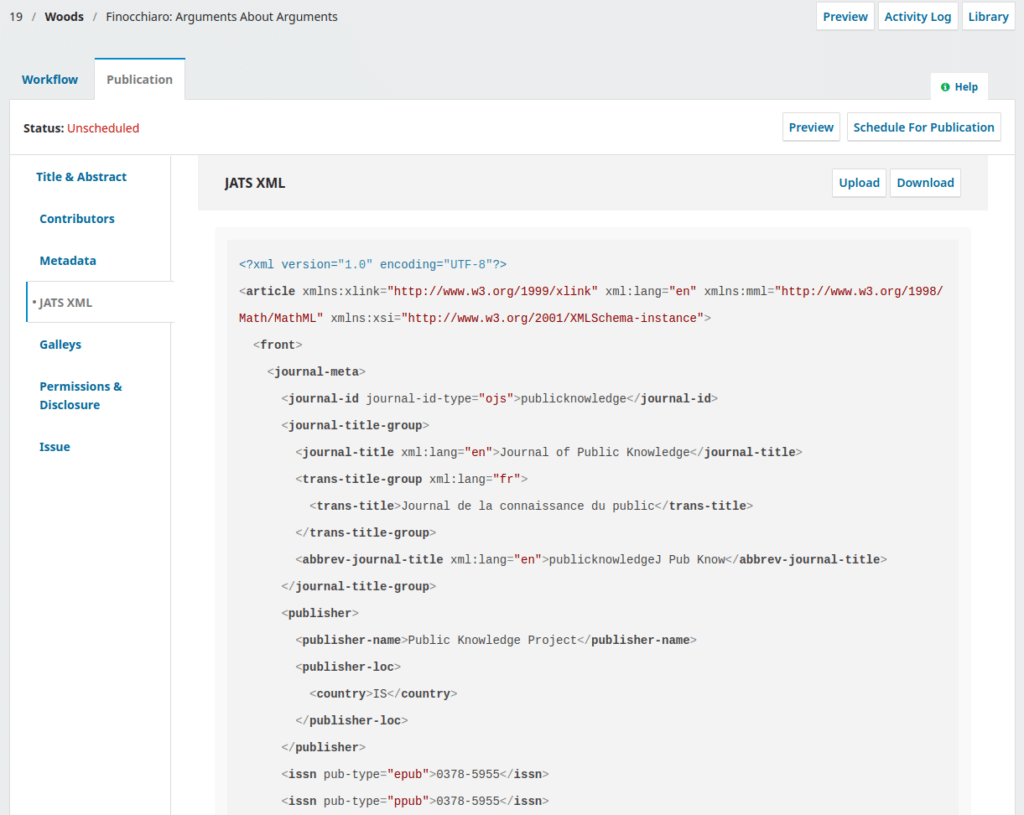

One of our developers, Dimitris, recently added a feature to OJS that’ll be pivotal for our XML work in coming years: a home for JATS documents to live, where anything that wants to interact with JATS documents can find them. OJS can either generate a limited JATS document on demand for those who don’t have them, or it can store one that’s been produced elsewhere. This will be released with OJS 3.5 and I’m sure it’ll become one of those features we’re shocked we ever had to live without.

We’ve also recently revitalized the XML working group around some fresh ideas – watch for more from them soon! We are hoping that we can reduce our dependency on a JATS editing tool while both simplifying the production pipeline and increasing opportunities to work with existing production-ready tools.

Alec, is there anything else you’d like to communicate to our audience?

While it might sound frustrating to work with JATS in practice, it’s an excellent standard and every piece of it reflects thoughtful work. It’s one of the rare standards that works globally and considers multilingualism from the ground up, for example. Whenever we have a question at PKP about how a piece of metadata should work, the JATS standard is often the first thing I consult.

While it has been hard for publishers with limited resources to adopt, and there is an exclusionary aspect to that, JATS has forced scholars to consider what scholarly documents are made out of, how we produce them through processes like peer review, and how we describe them. In that sense, JATS is a tremendous piece of meta-science. It is often at the center of the scholarly publishing ecosystem pushing for improvement.

Thank you Alec, for making JATS XML in the world of scholarly publishing understandable!

If you’d like to learn more about what PKP is doing, check out this plugin for OJS 3 that parses DOCX and converts it to JATS XML format, and this OJS3 Plugin for parsing JATS XML and displaying it on article detail page.

About Alec

Alec is the lead developer for all PKP infrastructure and the PKP Web Application Library, works with the community, and writes code. He has been working with PKP since 2005 and in that time has led sprints, taught workshops, and worked with editors everywhere except Antarctica (so far). Away from the computer, he loves running, drumming, cycling, community building, and making robots with his daughter.

Jump to other newsletter sections

📌 New to Archipelago? Check out our Introduction

📌 Celebrating 12 years of PITT-PKP Development Partnership