In 1998, I initiated a project that set out to make research a greater part of what constituted public knowledge. I called it a Public Knowledge project. That is, before PKP was PKP, it was PKp. The initial project arose out of a modest gift to the University of British Columbia from Pacific Press, the company that owned Vancouver’s two newspapers, the Vancouver Sun and Province. On learning of this gift to UBC, where I served as a Faculty of Education professor, I proposed that this new Pacific Press Professorship explore how the internet, with all its early promise as an “information highway,” could increase public access to research and scholarship. This would complement the Pacific Press’ journalism, I suggested, as well as advance educational goals, by expanding the storehouse of public knowledge.

The Vancouver Sun editor-in-chief, John D. Cruikshank, happened to attend the first public lecture I gave in the new professorship. He invited me to come by the paper and discuss with him and Sun reporters Gillian Shaw and Janet Steffenhagen how this public knowledge connection might work. We decided to collaborate on a newspaper series covering computers in education that would bring together the paper’s news stories (which were only on paper) and a website featuring relevant research studies for each story, along with an interactive forum led by an expert in the area.

This initial Public Knowledge project ran in the Vancouver Sun, April 24-29, 1999, with reporting on, among other things, gender discrimination in computer classes, shortfalls in technology funding for the schools, and the introduction of internet access in libraries. UBC graduate students Henry Kang, Lisa Korteweg, Brenda Trofanenko, and myself, had set up a website with links to research on, for example, the distance between information and understanding, and, presciently, the future of the electronic journal (thank you Wayback Machine). Now you might notice that these two studies fall decidedly short in matching the stories that were being reported. While we had come across plenty of far more relevant studies, we had run headlong into two issues. First, journals were making a slow migration to online publication. Second, and more importantly, publisher contracts placed limits on the library’s off-site sharing of research with the public. Some Sun readers moved from news stories to research studies, and a few joined the forums. We approached Pacific Press for more support, although by that point the company was owned by the notorious Conrad Black, so perhaps it was fortunate that his co-conspirator and Sun publisher David Radler was not moved by my case for this project. Still, we soon gave this type of Public Knowledge project a second go, this time in collaboration with the BC Teachers Federation and BC Ministry of Education on educational policy questions. Yet this only further convinced me that before universities joined forces with the news media, schools, government, and libraries in producing a greater democratic engagement with knowledge, they first had to get their own houses of learning in order.

As devoted as the academy was to conducting research in the public interest, what these initial experiments with public knowledge brought home to me was how these institutions were, in effect, producing an increasingly expensive and restricted private good. This had only been reinforced during the 1990s by the “serials crisis” with journal prices forcing libraries to cut subscriptions. My first response, in considering how universities could get on the side of public knowledge, was, to begin with, a clean sheet of paper. I began drawing up designs for ways of using the internet to enable publicly oriented scholarly publishing.

After faculty members in more than one setting made it perfectly clear that starting over was simply not an option after building their lives around the current journal world, it occurred to me that I might be able to help them with that existing world, given my recent experiences with online project management systems. This was through the education startup Knowledge Architecture founded earlier in the decade by Vivian Forssman. We were addressing the shortage of IT support in schools during the 1990s by designing online platforms that helped technically adept students both manage and deliver the assistance needed by teachers and students. While the company wrapped up before the end of the decade (as schools staffed up), what I learned of online dashboards and workflow management for students, could be applied, I realized, to what I knew of journals after many years publishing and presenting in the social sciences and humanities.

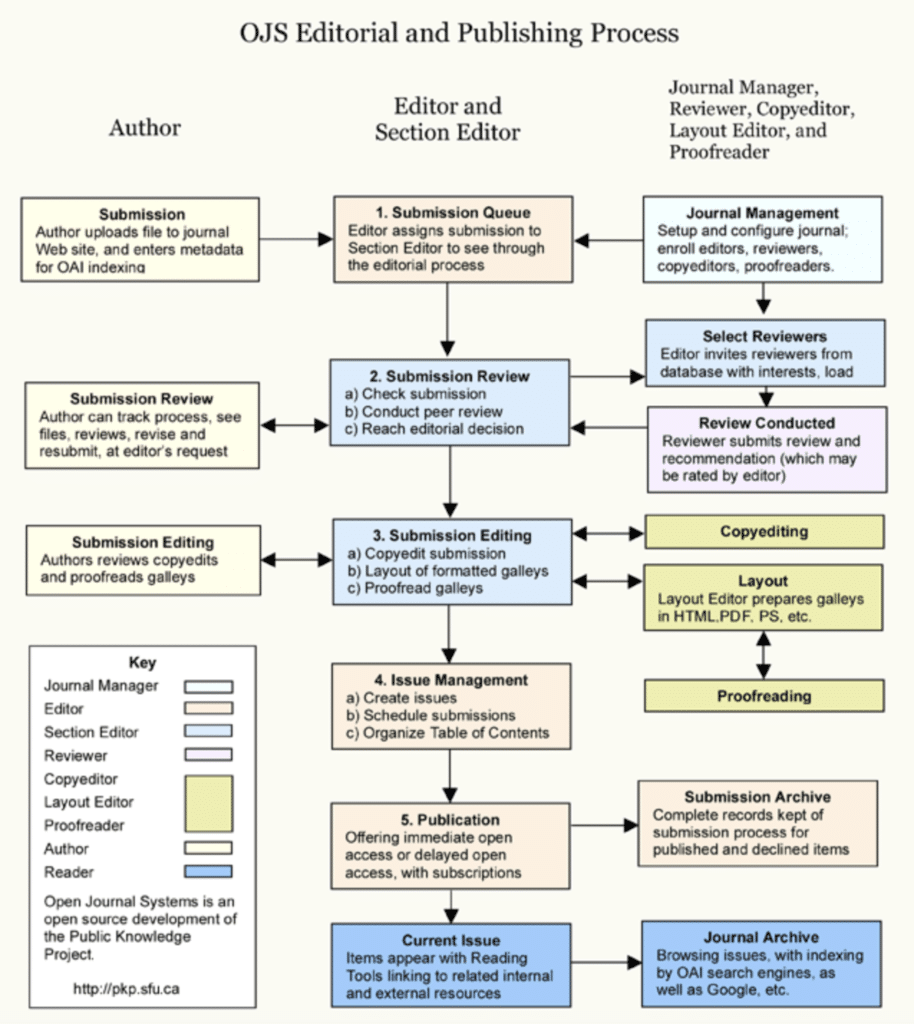

So I set out to design a publishing platform that would make it easier and cheaper for editors and publishers, as well as conference organizers, to manage, review, and distribute research online. Of course, these people had managed very little online at this point, and certainly not journals or conferences, so a warm and enthusiastic embrace was not to be expected. Still, I optimistically assumed that offering them an open-source and freely available scholarly publishing system would both help and encourage them to move in a similar direction. I returned to the blank page (and Word) to mock up stages and screens for running papers through conference and journal workflows, while drafting instructions and help for authors, reviewers, editors, and organizers (see early flowchart below). These workflows were then coded by a team of UBC undergraduates, led by Kevin Jamieson. The Public Knowledge Project released its first version of Open Conference Systems early in 2001, followed by Open Journal Systems in the spring of 2002.

For more on the history of PKP, see our timeline.